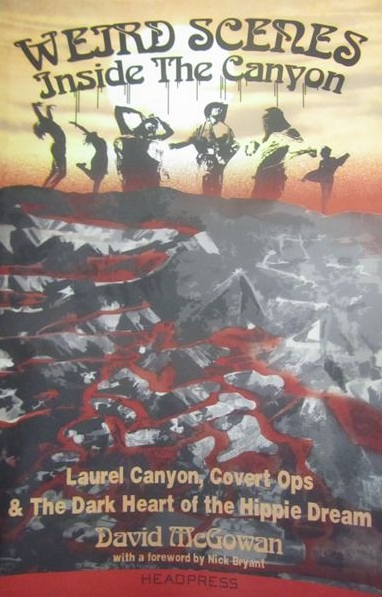

Extraction from the book: Weird Scenes: Inside The Canyon by author David McGowan

“For whatever reason—it’s still not understood by criminologists—

California in the 1970s was ground zero for serial killers.” Stella Sands, writing in The Dating Game Killer

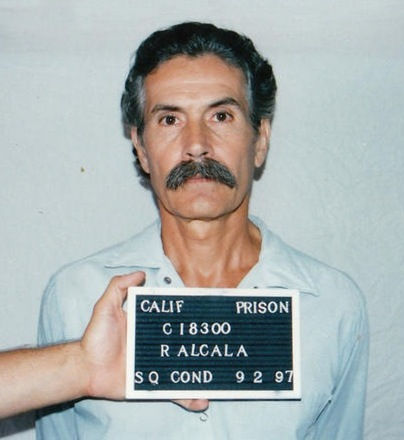

One thing that has become very clear while researching this book is that there are disturbing parallels between the Laurel Canyon saga and my previous research on the phenomenon of serial killers— research that led to my earlier book, Programmed to Kill. Nowhere is that more true than in the details of the curious case of Rodney Alcala, otherwise known as the Dating Game Killer, who is said to be one of the country’s most prolific serial killers. He has been convicted of seven murders, accused of several more, and some law enforcement officials have claimed, rather ludicrously, that he could be responsible for as many as 130 murders. It is only in recent years though that he has been identified as a serial killer, despite the fact that all the crimes he is accused of were committed in the 1970s.

In addition to being an alleged serial killer himself, Alcala allegedly operated on the same turf as a few other, more high-profile serial killers. And as fate would have it, he also had a number of connections to the Laurel Canyon scene and some of the key people and places that made up that scene. In other words, Alcala’s story seems to provide a bridge between the seemingly idyllic Laurel Canyon scene and the brutal world of serial murder.

In the opening chapter of Stella Sands’ The Dating Game Killer, that connection is hinted at:

“As cars cruised up and down Hollywood Boulevard and the Sunset Strip, radios blared edgier, angrier rock and roll: Masters Of War by Bob Dylan, What’s Going On? by Marvin Gaye, Eve Of Destruction by Barry McGuire. Musicians from bands like the Doors, the Byrds, Cream, and the Animals played the Whiskey-a-Go-Go [sic] on the Sunset Strip— and partied with wild abandon at the Chateau Marmont Hotel up the street... Amidst all this turmoil and social upheaval in 1968, an event occurred that is not well documented by the era’s historians: ‘Tali S.,’ age eight, was abducted on her way to school.”

This story begins though in 1943, in San Antonio, Texas, with the birth on August 23 of one Rodrigo Jacques Alcala-Buquor. Growing up, young Rodrigo (known as Rodney) attended mostly private Catholic schools where he got excellent grades and never showed any signs of being a problem child. In 1951, when he was about eight, he and his family moved to Mexico where he attended the American School. Not long after relocating, Rodney’s father left the family and returned to the States alone.

In 1954, after a few years in Mexico, Rodney and his mom and siblings relocated once again, this time to Los Angeles, California. By 1956, he was enrolled at the private Cantwell High School for boys, which later merged with Sacred Heart of Mary High School for girls to become the Cantwell-Sacred Heart of Mary High School, owned and operated by the LA Archdiocese.

Alcala finished out his senior year at Montebello High School, graduating in 1960. According to various reports, he had a wide circle of friends and never had any trouble lining up dates during his high school years. In addition to being an excellent student and talented athlete, he was on the yearbook planning committee and he took piano lessons. He was, in other words, a well-rounded and popular kid—the kind of young man you would expect to see voted “most likely to succeed” by his high school classmates.

On June 19, 1961, Rodney Alcala enlisted in the US Army. His older brother was at the time attending prestigious West Point Military Academy, which generally requires a nomination from a US Senator or a member of the House of Representatives. There is no explanation in the available literature as to how the Alcala family had either the financial means or the political connections to secure such an appointment.

Rodney meanwhile entered a program in North Carolina to become a paratrooper but instead served as a clerk, if his service records are to be believed. He was stationed, interestingly enough, at Fort Bragg, which had become, with the creation of the Psychological Warfare Center in 1952, a hotbed of research on ‘unconventional warfare.’ Fort Bragg is also the long me home of US Special Forces.

After two years of military service, Alcala unexpectedly showed up at his mother’s Montebello home after having gone AWOL. He was quickly hospitalized and informed that he was in immediate need of psychiatric treatment. Taken first to San Francisco, he soon found himself at a military hospital at the Marine Corps Air Station at El Toro, near Irvine, California. He remained there for an unspecified length of time.

Following his release, he returned to his mother’s home in Montebello and shortly thereafter enrolled in UCLA’s College of Fine Arts, from where he earned a degree in 1968. During his first year there, another young student who had just moved out from Florida—a guy by the name of Jim Morrison—likewise enrolled in UCLA’s College of Fine Arts. Both young men displayed a passion for making student films. According to Morrison biographers Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman, during Jim and Rodney’s time at the College of Fine Arts, a fellow student cut his girlfriend’s heart out.

On September 25, 1968, an eight-year-old girl later identified as Tali Shapiro was abducted while on her way to the Gardner Street Elementary School in Hollywood. At the time, according to Sands, Shapiro was “living temporarily at the Chateau Marmont Hotel in West Hollywood with her brother, sister, mother, and music-industry father.” The family was temporarily rubbing elbows with the likes of Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin because, as it turns out, “their home had recently burned down in a fire.”

As Gary Valentine Lachman has written, the hotel during that era was widely rumored to offer a decidedly unhealthy environment in which to raise a young girl: “Tales of pacts with the Devil followed [Led] Zeppelin throughout their career, and stories of orgies, black masses and satanic rites were commonplace, mostly centered around the infamous Chateau Marmont off the Sunset Strip.”

On the morning of her abduction, Shapiro is said to have woken early and, without informing her parents, decided on her own to walk to school rather than taking the bus—which seems difficult to believe given her young age and the fact that the school was a little over a mile away down seedy Sunset Boulevard. As the story goes, Alcala was spotted luring Shapiro into his vehicle by a good samaritan, who then followed Alcala back to his apartment where he called police from a nearby phone. The police though apparently didn’t rush over, giving Alcala to strip, viciously rape and then bludgeon the young girl nearly to death. She was so thoroughly battered, with her head bashed open and a heavy bar placed across her throat, that the responding officer initially thought she was dead.

(Alcala abducted Shapiro with a car without license plates on it)

Upon arrival, the officer knocked on the suspect’s front door and was greeted through the window by a partially naked man who claimed he had just gotten out of the shower and would need a minute to get dressed. Despite the fact that the officer was responding to a report of an abducted child (with the witness on the scene) and had just encountered the presumed suspect, he nevertheless allowed that suspect me to get dressed and escape. According to Sands, “In the short me it had taken to kick in the door, the perpetrator—the monster—had slipped out the back.” The LA Weekly concurred, claiming that Alcala “escaped through a backdoor.” Not many apartment units, it should probably be noted, come equipped with a back door.

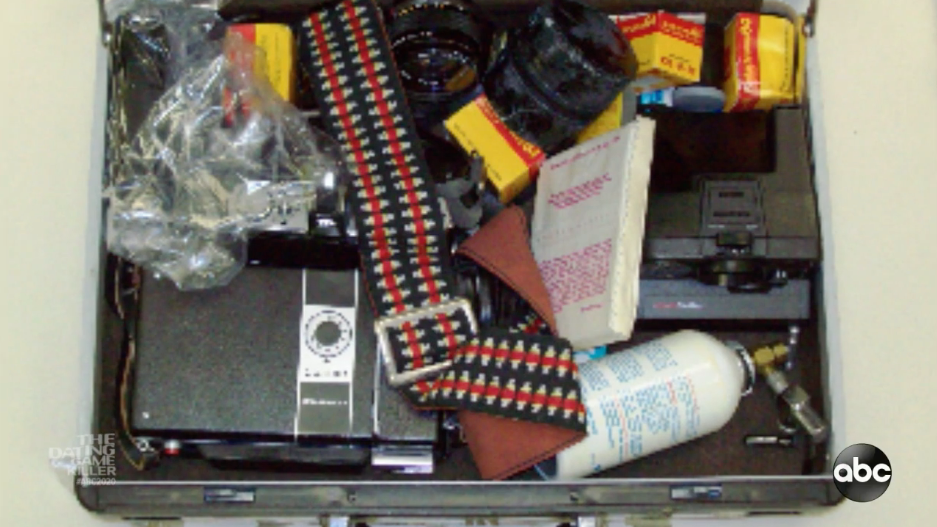

In any event, the apartment was found to be full of photographic equipment and stacks of photographs of young girls. The suspect, however, was nowhere to be found. The case was assigned to, of all people, LAPD detective Steve Hodel, brother of Michelle Phillips’ surrogate mom, Tamar Hodel, and son of accused Black Dahlia killer George Hodel. According to a January 21, 2010, article in the LA Weekly, Hodel was at the time a “newbie detective working juvenile crimes.” The Shapiro family, meanwhile, abruptly decided to relocate to Mexico, a move that is routinely cited as the reason the crime was never prosecuted.

Following his unlikely escape, Alcala immediately relocated to New York and, using the name John Berger, applied for admission to the prestigious New York University School of the Arts. Although the semester had already begun at the notoriously selective school, Berger/ Alcala was nevertheless admitted. He ended for three years, working at times as a security guard and, during the summers of 1969, 1970 and 1971, as an arts counselor.

One of Alcala’s instructors at the school was a guy who during those same years had a slaughter perpetrated at his home, and who Pamela Des Barres once described as being “definitely not normal,” Mr. Roman Polanski.

In June of 1971, Cornelia Crilley, a TWA stewardess who lived with her family across from the sprawling Cavalry Cemetary, was found dead. She had been in a two-year relationship with a Leon Borstein, then an assistant district attorney for Brooklyn who later became the chief special prosecutor for New York City. Borstein, who claimed that Crilley was the love of his life but who nevertheless married just a year after her murder, was initially the prime suspect. The crime appeared to have nothing whatsoever to do with Rodney Alcala—but a full four decades later, in 2011, he would be indicted for her murder.

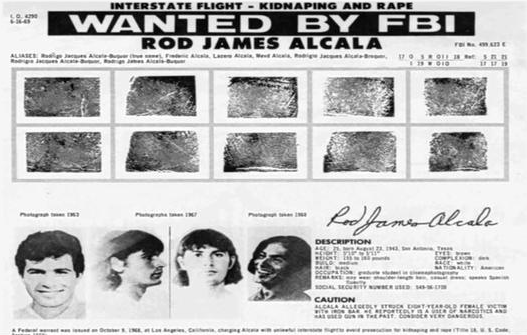

By the time of Crilley’s murder, Sands notes, “detective Steve Hodel and his LAPD team had been trying to locate Alcala for nearly three years.” They finally got a break when Alcala was added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list and was subsequently recognized by a couple of the teens at the camp where he served as a counselor.

Upon his arrest and return to Los Angeles, Alcala was facing very serious charges of kidnapping, rape and attempted murder, yet he was allowed to cop a guilty plea to a single count of child molestation, for which he received a sentence of one to ten years. He ultimately served less than three years, with much of that time spent at the notorious California Medical Facility at Vacaville.

Also housed at Vacaville during that time was Donald DeFreeze, who would soon emerge as Cinque, leader of the so-called Symbionese Libera on Army. According to Dr. Colin Ross, during that same time period, “the CIA was conducting mind control experiments [at Vacaville] under MKSEARCH Subproject 3.”

In August 1974, a prison psychiatrist recommended that Alcala be released and he was paroled to LA County and required to register with the local police as a sex offender. Within just weeks of gaining his freedom though, Alcala kidnapped a thirteen-year-old girl and was promptly arrested once again. He again caught a lucky break and was found guilty only of violating his parole and of furnishing drugs to a minor, escaping far more serious charges. He served about two-and-a-half years and was paroled on June 16, 1977.

Just days after being released, he asked his parole officer for permission to take a trip to New York City, and, since he had behaved himself so well the last time he was on parole, his request was granted.

Alcala remained in New York for a little over a month, ostensibly to visit relatives. During his time there, a woman by the name of Ellen Jane Hover went missing. Being the small world that it is, Ellen just happened to be the daughter of Herman Hover, who had been the long time owner of Ciro’s on the Sunset Strip, the club that famously launched the career of the Byrds. She was also the goddaughter of Sammy Davis, Jr. For reasons that were never explained, the FBI took a keen interest in Hover’s disappearance, which happened to come at a time when New York City was gripped by intense fear. It was, after all, the infamous ‘Summer of Sam’ and Hover’s disappearance on July 15, 1977, was sandwiched between two Son of Sam attacks, one on June 26 and another on July 31.

Hover remained missing for almost a full year, until her skeletal remains were discovered in June of 1978, in a shallow grave on, of all places, the Rockefeller estate in Westchester County. It would be over three decades later that Rodney Alcala would be charged with her murder.

Upon his return from New York, Alcala applied for a job as a typesetter at the Los Angeles Times. He applied using his real name and was promptly hired, despite having been twice convicted for felony offenses, having served time for crimes committed against children, being a registered sex offender, being on parole, and holding the distinction of once numbering among the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted. A coworker would later say, perhaps tellingly, that Alcala seemed like he knew a lot of famous people.

On November 10, 1977, the nude, brutalized body of eighteen-year- old Jill Barcomb was found posed on a side road adjacent to, and in full view of, the Marlon Brando estate overlooking Laurel Canyon. The murder was investigated by LAPD detective Phillip Vannatter, who would later famously tote a vial of blood around with him while investigating the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman.

For many, many years, Barcomb’s death was credited to the Hillside Strangler team of Angelo Buono and Kenneth Bianchi. Like the Strangler victims, Jill was found nude, strangled, tortured, sexually assaulted, bound and posed on a hillside. And her death occurred amidst a string of Strangler killings—Judith Miller on October 31, Lissa Kastin on November 6, Barcomb on November 10, Kathleen Robinson on November 18, and Kristina Weckler, Delores Cepeda, and Sonja Johnson all found dead on November 20. In addition, Barcomb knew Strangler victim Miller. Nevertheless, the murder would eventually be credited to Alcala, but not for nearly forty years.

According to the official version of events then, Judith Miller, chosen at random, was killed on Halloween by a pair of serial killers. And then a mere ten days later, in an officially unrelated event, her friend Jill Barcomb, also chosen at random, was killed by a different serial killer who, despite being unconnected to the other two serial killers, nevertheless killed and posed Barcomb in a manner remarkably similar to the way Miller was killed and posed. One has to wonder what the odds of that actually happening would be.

In any event, Jill Barcomb, found not far from where Marina Habe had been found nearly a decade earlier, is yet another tragic addition to the Laurel Canyon Death List. As is, I suppose, Ellen Jane Hover. Tali Shapiro narrowly avoided making the list.

At the request of the FBI, Alcala was brought down to the LAPD’s Parker Center in December 1977 for questioning concerning the still-missing Ellen Hover. He admitted knowing Hover and even acknowledged being with her on the day she vanished, but he claimed to know nothing about her disappearance. That same month, twenty-eight-year- old nurse Georgia Wixted was found brutally murdered in her Malibu, California, bedroom. For nearly thirty years, there would be absolutely nothing linking Rodney Alcala to the crime or the crime scene.

In early 1978, Alcala was questioned by the Hillside Strangler Task Force, which was composed of members of the LAPD, the LA Sheriff’s Department and the Glendale Police Department. He was arrested at that time, though only for the benign offense of being in the possession of marijuana, for which he served a brief jail sentence. For a time though, he was considered a “person of interest” to the task force. On June 23, 1978, just after Alcala’s release from that brief jail stint, the savaged body of thirty-two-year-old legal secretary Charlotte Lamb was discovered on the floor of an apartment laundry room in El Segundo, California. Once again, there was no evidence linking Alcala to either the crime, the victim, or the crime scene, and he would not be named as a suspect for some twenty-five years.

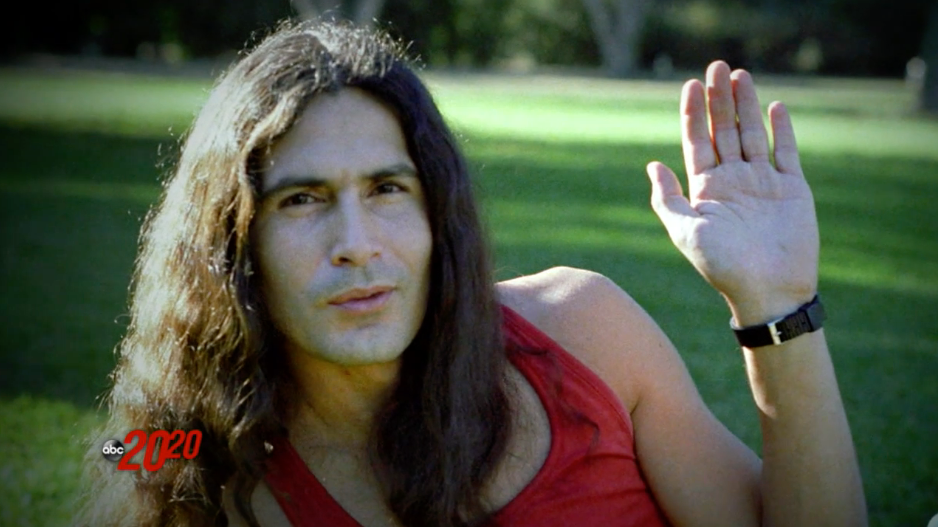

On September 13 of that same year, Alcala infamously appeared as Bachelor #1 on television’s The Dating Game. Despite his criminal history and sex offender status, which surely would have been discovered during the show’s screening process, he was presented to women across the country as one of the nation’s most eligible and desirable bachelors. The guy doing that presenting was Dating Game producer Chuck Barris, who has stated publicly that he was a CIA asset at the time the show was in production and that the show itself was essentially an elaborate CIA front designed to provide cover for Barris’ own travels and activities. Mr. Barris was also, according to some reports, a onetime resident of everyone’s favorite canyon.

On February 13 of the following year, Alcala picked up a fifteen-year- old hitchhiker by the name of Monique Hoyt, who voluntarily spent that night at Alcala’s home. The next day, Valentine’s Day, thirty-four-year- old Rodney Alcala took fifteen-year-old Monique Hoyt into the woods to shoot nude photos. At some point the situation turned violent and nonconsensual, resulting in yet another arrest for Alcala. Though facing very serious felony charges, including kidnapping, rape, and the production of child pornography, his bail was set at a paltry $10,000. At the end of April, Alcala gave his two-week notice to his superiors at the LA Times. How he had managed to keep his job through his jail sentence for marijuana possession and his arrest for kidnapping a young girl is anyone’s guess. The Times apparently used the same screening service as The Dating Game.

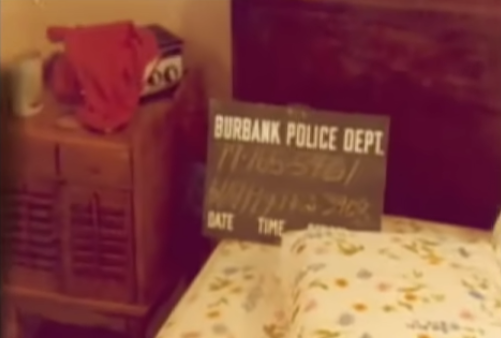

On June 14, another young woman, twenty-one-year-old Jill Parentau, turned up dead in her Burbank, California, apartment. Once again, there was no evidence linking Rodney Alcala to the crime and Parentau’s murder would remain unsolved for two-and-a-half decades. Six days after her murder, on the eve of the summer solstice, twelve-year- old Robin Samsoe of Huntington Beach, California, went missing after spending time at the beach with her best friend.

Offcially, her remains were discovered twelve days later in a heavily wooded area allegedly chosen by Rodney Alcala. But the reality appears to be that it is unknown what became of Samsoe. What is known is that from the time of her disappearance, authorities took a much different approach to dealing with Alcala than they had in the past. Before a month had passed, he was back in prison and would never walk free again.

As the story is generally told, Samsoe was strolling the beach with her friend when they were approached by Alcala with a request to take their photos, ostensibly for a student photo contest. A neighbor who happened to be passing by approached the trio, at which time Alcala lowered his head and quickly shuffled off. The girls went about their business without giving the incident much thought and Samsoe soon said goodbye to her friend. Borrowing the friend’s bike, she headed off to a ballet class that she never made it to.

On the afternoon of July 2, a worker with the US Forestry Service discovered human skeletal remains in a heavily wooded section of the Angeles National Forest. The area was littered with discarded beer bottles and cigarette butts. The remains appeared to be those of an adult, and investigators, according to a June 1989 article in Orange Coast Magazine, believed the death to be “drug-related.” The crime scene, according to the same report, “was given only a cursory examination by the Los Angeles Sheri ’s Department.” Five days later an LA County coroner decided that the remains were actually those of a child. And not just any child, but the missing Robin Samsoe.

Unexplained was how the remains of a child could have been mistaken for those of an adult. Also unexplained was how the child could have been reduced to skeletal remains, completely stripped of flesh and hair, in an absurdly short amount of time.

The only thing that would ever tie Rodney Alcala to those scattered remains would be the testimony of one Dana Crappa, a twenty-year-old seasonal firefighter with the Forestry Service. And it is here, with the introduction of Dana Crappa, that this story grows very murky. As Orange Coast Magazine noted, “The exact bit of information that first tied Crappa to the disappearance of Robin Samsoe is not known.” Indeed, there doesn’t appear to be anything that initially tied Crappa to Samsoe. But with considerable molding by police, Crappa would emerge as the star witness for the prosecution.

For reasons that have never been adequately explained, Huntington Beach Police called Crappa in for questioning on August 2, 1979, exactly one month after the discovery of the remains. At that time, Crappa was shown photos of Alcala and Samsoe as well as of Alcala’s car. She told investigators that she had never seen the man or the girl before, but that the car might resemble one she had seen parked near Mile Marker 11 (near where the remains were discovered) on either June 7 or June 14 at around 9:30–10:00 PM. Seeing as how the dates provided by Crappa were well before Samsoe’s disappearance, this information was of no use to police. The time of day was entirely wrong as well.

Pressed by police to state whether it might have been June 20 or June 21 when she saw the vehicle, Crappa responded that it “definitely could not have been.”

On August 7, Crappa was again questioned by police. Miraculously, on this occasion she recalled that she had seen the vehicle similar to Alcala’s on June 21, and had done so between 8:00 and 8:30 PM! She added that, prior to her discovery of the remains on July 2, she had no awareness of the crime scene. But at preliminary trial proceedings not long after that meeting, Crappa told a different version of her story; she again said that she had seen the car on June 21, but she now claimed that it had been between 10:00–10:30 PM. She added that she had not seen anyone near the parked car. She also added that she had first seen the corpse on June 29, several days earlier than she had previously claimed. And she added that the corpse was already skeletal at that time.

On February 7, 1980, Crappa met with Huntington Beach Police detective Art Droz and a police psychologist named Larry Blum. She had, however, previously stated that she wanted no further interaction with the police so she was deliberately not told that the men she was speaking to were police personnel. Although authorities heatedly deny it, it is painfully obvious that Ms. Crappa was subjected to hypnotic interrogation techniques during that meeting and at future meetings. According to police, at the February 7 meeting she claimed that she had seen the vehicle on June 21 and that she had in fact seen a man by the car after all! She also said that when she had returned on June 29 she had found clothes strewn about the area, a crusty knife, and six .22-caliber bullet casings. For reasons never explained, she also claimed that she had picked up the bullet casings and thrown them away!

By that time, Crappa’s testimony was so ridiculously riddled with contradictions and inconsistencies that it should have had no value to prosecutors in any kind of real trial. Police and prosecutors though weren’t quite done with her.

On February 11, she once again unknowingly spoke to police investigators. On February 15, she met with a detective and one of the prosecutors on the case. By then she was claiming to have seen the car on June 20 and to have seen a man guiding a young girl away from the car and into the woods! On the day that meeting was held, the presiding judge ruled that Alcala’s prior offenses would be allowed into evidence, including the fact that Alcala was suspected of involvement in Hover’s death, a crime he had never even been charged with, let alone convicted of. As Sands noted, “The ruling was a momentous victory for the prosecution. Because there was little direct evidence linking Alcala to the Samsoe crime, the prior attacks would lend credence to their case.” It was becoming perfectly obvious that Rodney Alcala was not going to get anything resembling a fair trial.

On February 26, Crappa once again met with detectives and prosecutors. Somewhere around that time she reportedly suffered a nervous breakdown and allegedly became suicidal, leading to her being involuntarily institutionalized. That, needless to say, must have greatly facilitated the process of programming the witness. A defense psychiatrist by the name of Albert J. Rosenstein would later describe Crappa in open court as “a Manchurian candidate at a minor level.”

As Alcala’s trial got underway on March 6, 1980, the defendant was paraded into the courtroom in cuffs and leg shackles in a deliberate attempt to prejudice the jury. But the real “linchpin of the trial,” as Sands wrote, “would be the testimony of one Dana Crappa, twenty-one.” On the stand, Crappa’s demeanor was odd, to say the least. She frequently took long, awkward pauses—when she wasn’t staring blankly into space. According to Orange Coast Magazine, her demeanor was so bizarre that the trial judge considered ending her testimony prematurely. She did though tell the story prosecutors wanted her to tell—a story that bore no resemblance whatsoever to the story she told when first mysteriously contacted by police.

In court, Crappa claimed that she had seen the suspect’s vehicle on June 20. She also said that she had seen a man resembling Alcala guide a young girl who resembled Samsoe into the woods. Although she had found what she allegedly observed disturbing, she acknowledged that she had told no one of the incident. When her curiosity got the best of her, she said, she had returned to the area on June 25 to have a look around. At that me, she had allegedly seen Samsoe’s body, decapitated and with part of her face gone. She had, of course, returned by herself and told no one of her supposed discovery. Crappa further told the jury that she had returned a second me on June 29, again alone. On that visit, she claimed, she had observed that Samsoe’s body had been reduced to a pile of bones. In just four days! Following that extremely unlikely second visit, she again, of course, told no one. We are apparently to believe then that she was brave enough to return to a remote murder scene alone on two occasions, but not brave enough to report her discoveries, even anonymously.

Crappa’s testimony had no credibility whatsoever, and she was not the only seriously dubious witness trotted out by the prosecution. There were also Robert J. Dove and Michael Herrera, a pair of Orange County jail inmates, both of whom testified that Alcala had given them jail- house confessions. A third OC inmate, however, testified that he, Dove and Herrera had fabricated the confessions to gain favor with authorities. What the jury didn’t hear was that all three inmates just happened to be clients of Alcala’s first court-appointed attorney. Of the thousands of inmates in the OC jail, Alcala had supposedly chosen to confess his crime only to three guys who happened to be represented by the guy who was supposed to be defending him.

Despite their best efforts, prosecutors were unable to present any physical evidence at all tying Alcala to the murder of Robin Samsoe; there was no fingerprint evidence, no fiber or hair evidence, no blood evidence, and no DNA evidence. There also don’t appear to have been many witnesses who weren’t delivering brazenly perjured testimony.

After a half-hearted defense that included alibi testimony from Alcala’s girlfriend and two of his sisters, followed by closing arguments and jury instructions, deliberations began on April 29, 1980. Jurors returned the next day with a guilty verdict on the charge of first-degree murder. The date was, of course, April 30 (Walpurgisnacht/Beltane)—because that’s just the way these things always seem to work. The penalty phase of the trial was a perfunctory affair with just two witnesses appearing for the prosecution, both of them parole officers to whom Alcala had previously reported. He was quickly sentenced to death.

At Alcala’s first appeal hearing, inmate Joseph Drake took the stand to repeat his claim that he, Dove and Herrera had fabricated Alcala’s confessions in order to strike an “informer’s bargain” with authorities. He was joined by Dove, who freely admitted on the stand that his previous testimony had been perjured. The inmate testimony had been crucial to the prosecution’s goal of adding the special circumstance of kidnapping, which was necessary for the imposition of the death penalty.

On May 28, 1981, the presiding judge issued an extraordinary ruling stating that there had been no “perjured evidence introduced during the trial, and that even had there been, that was not a substantial consideration on regarding Alcala’s guilt.” (emphasis added)

The special circumstance of kidnapping, therefore, would stand and Alcala was returned to Death Row. On August 23, 1984, however, the California Supreme Court ruled that the lower court had erred in allowing into evidence Alcala’s prior offenses. Rodney Alcala would be getting a new trial after all. The available literature invariably expresses outrage over this reversal, claiming that the allegedly criminal-coddling ‘liberal’ courts let him off on “a technicality,” though that is far removed from the truth.

In April of 1986, Alcala’s second trial for the murder of Robin Samsoe got underway. There was a problem though: Dana Crappa, whose testimony was the only hope the state had of getting a conviction, privately informed the judge that she would not be able to testify because she remembered nothing about the incident. She also told him that she did not remember previously testifying, which isn’t surprising considering that she delivered that testimony in an obviously induced mental state. Signaling that this trial was going to be just as much of a sham as the first trial, the judge ruled that he would allow Crappa’s previous testimony to be read into the record without Crappa being present. That, of course, deprived the jury of the ability to judge Crappa’s demeanor and body language and all the other non-verbal clues that jurors use to gauge someone’s honesty and credibility. It also denied the defense the opportunity to cross-examine the witness and confront her with her wildly varying accounts of the incident.

The remainder of the trial largely followed the pattern of Alcala’s first trial, with a number of women—including Alcala’s mother, two sisters, and a female coworker at the Times—providing testimony for the defense. The jury once again returned with a guilty verdict and he was once again sentenced to death, but only after blasting his attorneys in court for being “unprepared and unwilling” to mount a real defense. Some six years later, on December 31, 1992, the California Supreme Court affirmed Alcala’s second conviction. And that, for the next decade or so, would be the end of the Rodney Alcala saga.

That all changed on March 30, 2001, when a federal district court set aside Alcala’s second conviction based on the wildly improper introduction of Crappa’s prior testimony. The court also opined that the defense had been improperly prohibited from introducing evidence that Crappa’s testimony had been induced. On June 27, 2003, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the decision of the federal court and vacated Alcala’s conviction, additionally citing the failure by police to secure and properly investigate the crime scene.

The stage was now set for Alcala to stand trial for the third time for the murder of Robin Samsoe. The state though was facing quite a dilemma: for whatever reason, there was still a very strong desire to have Alcala take the fall for Samsoe’s disappearance, but there was no semblance of a case left. There would be no perjured inmate testimony. There would be no induced testimony from Dana Crappa. There would be no inflammatory admission of prior uncharged crimes. There would be no parading of Alcala in handcuffs and leg shackles. And there still was not a shred of physical evidence tying Alcala to the crime or the alleged crime scene.

On October 17, 2003, Alcala led a motion to act as his own attorney in the coming trial. This was cast by the media as a misguided, narcissistic attempt by Alcala to put himself in the spotlight. In truth, he was undoubtedly aware that he had been sold out twice before and likely would be again. Indeed, in June 2003, the very month that Alcala’s conviction had been vacated, DNA evidence had supposedly identified him as the killer of Georgia Wixted. The state was going to be taking a novel approach to railroading Alcala this time.

Alcala would soon allegedly be linked by DNA evidence to the Lamb, Parentau and Barcomb murders as well. Like Wixted, they were all killed in Los Angeles County, which is under a different court jurisdiction than Orange County, where Alcala had previously stood trial for Samsoe’s murder. All five cases were handed off to a grand jury, which, as California grand juries do, met secretly to render a decision. According to Sands, “After hearing all the evidence against Alcala, the grand jury came down with an indictment. Although Lamb, Parenteau, Barcomb, and Wixted had all been murdered in Los Angeles County, the grand jury held open the possibility that prosecutors could consolidate all five cases—including that of Robin Samsoe—and try Alcala in Orange County.”

After numerous delays, the consolidated trial began in Orange County in early 2010. It was the first time, and to date the last time, that such a cross-county consolidation had been allowed. The state was now going to try to convict Alcala for the Samsoe murder by presenting it as one of a string of murders, with the other four allegedly being open- and-shut, scientifically unimpeachable cases. It appeared that judicial malfeasance had now reached such a level that the state had dusted of four very old murder cases and manufactured evidence linking Alcala to them as a way of garnering a conviction for a fifth murder that was otherwise not prosecutable.

Alcala was by then being widely identified by police and the media as a prolific serial killer who was likely responsible for other, undiscovered murders. Some of the most over-the-top media coverage came from the UK, where a February 2010 headline in the Telegraph declared that “US serial killer Rodney Alcala could be ‘new Ted Bundy.’” An April 2010 headline in the London Daily Mail was even more histrionic: “The ‘most prolific’ serial killer in US history is sentenced to death as police fear he could be behind 130 murders.”

At Alcala’s third trial, a fingerprint technician testified that a palm print recovered from the scene of Georgia Wixted’s murder thirty-three years earlier was a match for Rodney Alcala. Another technician testified that blood evidence recovered from another of the murder scenes also was a match. Nobody though bothered to explain why Alcala was just then being identified as the perpetrator of these crimes if the evidence linking a known violent sex offender and ‘person of interest’ to the murders had supposedly been in existence for more than thirty years!

Craig Robison, one of the lead detectives on the Samsoe case, testified that he had arrested Alcala on July 24, 1979, and taken him down to the station while other Huntington Beach officers executed a search warrant on the home. It was at that time, according to Robison, that a Sergeant Jenkins had allegedly discovered a receipt for a Seattle storage locker. Rather then seize the receipt, however, he purportedly left it there and copied down the information on it. The actual receipt was never produced at trial and there is no way of verifying that it ever existed.

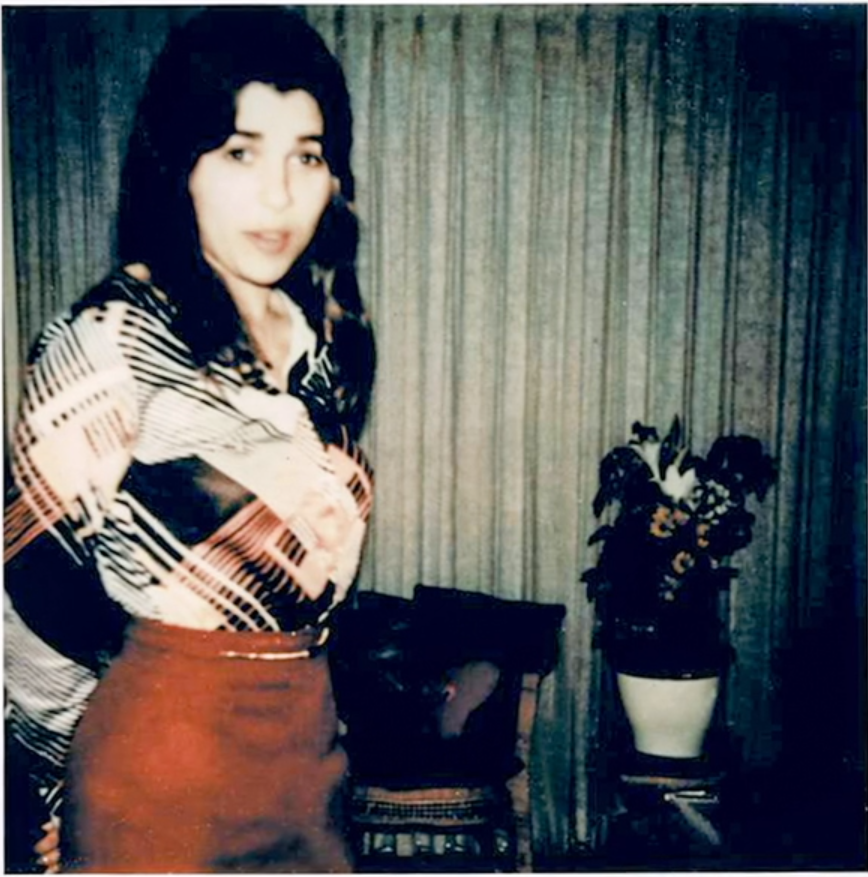

Following that seriously dubious lead, detectives had discovered a storage unit purportedly filled with photographs and other evidence Alcala had stashed there. Immediately after the discovery of Samsoe’s alleged remains, Alcala is said to have driven to Seattle and deposited the items in the unit, after which he stayed overnight and then drove back home. He had, of course, told no one of this alleged trip and no witnesses could place him in Seattle. And there was no explanation for why he would have driven all the way there, to a city he had no known connection to and was not known to have ever visited, to stash the items. Police would later try to connect Alcala to murders previously attributed to Seattle’s so-called Green River killer.

Alcala was, needless to say, convicted a third time for the murder of Robin Samsoe, as well as for the murders of Lamb, Wixted, Parentau and Barcomb. On March 2, 2010, the penalty phase of the trial began. A week later, on March 9, the jury returned once again with a recommendation that Alcala be executed. Three weeks later, the presiding judge formally sentenced him to die by lethal injection.

Six months after that third conviction, the television show 48 Hours Mystery aired The Killing Game, a look at the Rodney Alcala case that had been produced by long me correspondent Harold Dow. The episode was aired posthumously; Dow had died suddenly and unexpectedly a month earlier, on August 21, 2010, just before completing work on the project. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that Dow had discovered something about the Alcala case that those with vested interests did not want aired on national television.

Whether or not Alcala’s third convicton in California will stand remains to be seen. Probably as a fallback option in case the convictions are once again overturned, as they certainly should be, Alcala was indicted in 2011 and subsequently convicted in New York for the murders of Crilley and Hover, though it is unclear what evidence those convictions were based on. Over the last several years, authorities have circulated scores of Alcala’s photographs in an attempt to link him to additional crimes. To date, not one of those photos has been linked to any known murders or missing persons cases.

So what, at the end of the day, are we to make of Alcala’s curious connections to the Laurel Canyon ‘peace, love and understanding’ scene? If his official bio is to be believed, his first victim, the daughter of a record executive, was snatched from the mouth of the canyon. One of his last victims was left posed at the northern end. And all along the way, such names as Jim Morrison, Roman Polanski, Marlon Brando and Steve Hodel, and such iconic places as Ciros and the Chateau Marmont, unexpectedly pop up in the storyline.

Rodney Alcala’s story is a strange one even by serial killer standards. But it is far from being the only serial killer story that the mainstream media got wrong. Interested readers can find a wealth of such stories in my previous book, Programmed to Kill.

Author Alan R. Warren who wrote the book: The Killing Game actually stated that Rodney Alcala had multiple personality disorder (DID)

You may be familiar with a recent movie that just dropped on Netflix called “Woman of the Hour” with Anna Kendrick. It is the fictionalized version of a true story about a serial killer and rapist name Rodney Alcala. He’s known as the “Dating Game Killer.” There have been countless shows, documentaries, and podcasts about his crimes. He was convicted of murdering 7 girls and women and placed on death row until he died of natural causes in 2021. And while he was convicted of some of his crimes, there was always a belief by investigators that he was potentially responsible for 130 more. One of those unsolved crimes involved Niki Rowe Cross. She says Alcala was one of the johns who raped her in an attic in Akron, Ohio in 1977 where she was held captive as a teenager along with two other teens for a year. Niki tells her powerful and disturbing story as a way to bring awareness to human sex trafficking and to help others.

https://agelesswithamandalamb.libsyn.com/site/niki-cross-human-sex-trafficking-survivor-of-rodney-alcala-speaks-about-the-horror-she-endured